Published in St. Louis American, December 19, 2019

All holidays in the U.S. are highly commercialized. Christmas is the most commercialized to the tune of $475 billion, according to National Retail Federation estimates. Lost in those billions is a big portion of the $1 trillion-plus spending power of black folks. Our consumerism rarely comes with demands for accountability and respect.

All holidays in the U.S. are highly commercialized. Christmas is the most commercialized to the tune of $475 billion, according to National Retail Federation estimates. Lost in those billions is a big portion of the $1 trillion-plus spending power of black folks. Our consumerism rarely comes with demands for accountability and respect.

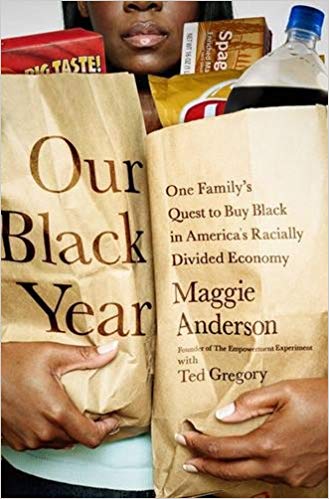

Some of us think about how fast our dollars literally fly out of our communities while other ethnic groups’ dollars circulate longer and benefit them more. It really smacked me in a different way when I heard Maggie Anderson speak at a program hosted by the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists. I bought her book, “The Black Year.” I felt the same energy and passion in those pages that I saw and felt at the podium during Anderson’s presentation.

Anderson and her husband John also thought about black dollars and where they get spent. The successful, professional couple took their concerns and complaints to another level. The Chicago family decided to embark upon an experiment to buy black for one year. Did they ever get a huge awakening!

It started off as The Ebony Experiment until the folks at Johnson Publications acted as if it had a monopoly of the word “ebony,” as in Ebony Magazine. Not wanting a big fight before the initiative got off the ground, the Andersons and their board reluctantly changed the name to The Empowerment Experiment. I personally favor the latter because the experiment was about economic empowerment, not just a color.

A few insights of their journey – like the number of black-owned grocery stores – may be sad, though common knowledge. The number of stores plunged from 6,339 at the turn of the segregated 20th century to about a half dozen today. The number of black-owned banks went from 130 during the post-slavery/Reconstruction period to a fluctuating 20-something today. Many may not know the actual statistics but still live the daily reality of resource scarcity.

The Anderson saga is not just a whimpering tale of scarcity rooted in racism and economic privilege. It attempts to unearth the complicated reasons for the lack of support of black businesses by black folks. It highlights the unsuccessful struggles of black businesses trying to fill voids.

While reading the book, I wanted to go to Chicago just to support Brother Karriem and his Farmer’s Best Market. His attempt mirrored similar local attempts like Yours Market. Their story also exposes the way racialized capitalism creates barriers (laws and practices) in a so-called free market system.

The whole experiment was one big, continuous struggle from getting sponsors to finding worthy black-owned businesses to support to fundraising to dealing with black attitudes rooted in internalized oppression as in Mista Charlie’s ice is colder.

Maggie Anderson was unapologetic in her criticism of black businesses whose products and practices showed a disrespect for black shoppers and the community it was supposed to serve. That’s why I believe it’s not just about buying black. There are non-black businesses who hire black employees, treat them and customers fairly, and who support racial justice and equity.

The Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University did the evaluation of The Empowerment Experiment. The Anderson’s family made 513 purchases during their Black Year with black businesses totaling nearly $50,000. Adding their transfers of investments to black financial institutions, the amount surged to $94,000. The case was made: Black dollars spent intentionally created capital.

The Black Year gives us a call to action, some hard-learned lessons and some tools like Maggie’s Tips for Buying Black the EE Way. The book admits the limitations of the experiment, but the journey’s outcomes reinforced the impact when black consumers change their spending habits.

Understanding economic power must be taught at an early age if the black community expects to create intergenerational wealth and financial stability, our civic leaders and elected officials must learn how to leverage our economic power when they’re at the negotiating tables. I could write an entire column about the lack of dollars black media outlets get from corporate entities and big-budget political campaigns.

Our communities are at a place where we can no longer depend on the good graces of government. It has no grace, no conscience, no remorse. The vision for a future of black prosperity is ours to develop and implement. Failure is not an option.